Tackling curriculum complexity with cognitive audits

A strategy for teachers, teams and instructional leaders

On Curriculum Complexity

Isobel Stevenson wrote a terrific newsletter post recently on the complexity of teaching, differentiating it from the term complicated because of unpredictability (read: classrooms are not machine like) and the need for adaptive expertise in addition to technical nous.

Within this broader definition also lies curriculum complexity, which is the way the cognitive elements within a curriculum interact with each other. While curriculum documents work to provide descriptors of knowledge and skills, these are often in the form of long lists or vague descriptors, which do not necessarily explain the inter-relationships between these elements that is required for disciplinary understanding. For example, what is the relationship between the identification of rhetorical techniques and argumentative justification in an English classroom? Does the second depend on the first, or is it bidirectional?

It is not always easy to discern, but the clearer idea a teacher has, the more focused their instruction.

Unpacking the cognitive domain of the curriculum therefore should be the first step of curriculum translation, yet in the rush to design instructional strategies and assessments, teachers often lack the time to linger in this initial stage. This can result in ‘planning on the fly’, or a lack of alignment between learning objectives and activities.

A slow, purposeful examination of cognitive relations not only avoids the superficial planning alluded to above but also provides a means to address the issues of curriculum complexity. It is also extremely useful for teachers new to a subject or unit. For this post, I am going to refer to senior year study designs for Year 11 and 12 where the curriculum translation stakes are extremely high given the role ATAR currently plays in the final year of schooling.

High Element Interactivity

In recent years, there is an increased propensity in study designs towards high element interactivity, not only in the content, but within the assessment tasks or question types. The definition from cognitive load theory explains how ‘high element interactivity, or complexity, occurs when more elements than can be handled by working memory must be processed concurrently’ (Chen et al. 2023)

For example, most senior curriculum tasks and examinations feature multi-modal extended response tasks which require multiple sources of information to be processed simultaneously. Consider the following extended response tasks VCE colleagues at my school in the HPE and Arts faculty are tasked with designing units for:

The complexity in both extended responses lies in students facing significant cognitive load by having to simultaneously retrieve and apply their disciplinary knowledge, comprehend and evaluate novel source material, while employing written conventions to synthesise and communicate their understanding. Furthermore, there is ambiguity in the curriculum language. What interrelationships? What meanings and messages?

In short, multiple cognitive hoops to jump at the same time.

To this end, teachers need significant time and support to not only unpack the complexity of their study designs, but also to construct ways to negate it for their students.

What I will share in this post is how I have used cognitive audits to support senior colleagues in spending longer in the first stage of curriculum translation, enabling better clarity of purpose which aids in difficulty reduction, hopefully mitigating the impact of high element interactivity.

Cognitive Audits

Part 1: Articulating the elements of the cognitive domain in learning objectives

A cognitive audit initially invites teachers to identify (through curriculum analysis, exam specifications and their own experience) the precise elements of the cognitive domain that a student must demonstrate within a unit of work. Focusing on student thinking as a first stop avoids several pitfalls such as planning around engagement activities or simply to ‘get through content’ and also provides an organising framework to reduce the opacity of the curriculum.

The cognitive domain (as per Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy) refers to the knowledge dimension and cognitive processing dimension.

While teachers need to be aware of the two dimensions when writing objectives, they need to ‘audit’ these objectives to be even more precise and situate the thinking within its context. This is the advice given by Dr Peter Ellerton at the University of QLD in his workshops on Teaching for Thinking, who first introduced me to the idea of a cognitive audit. His proviso to ‘think and plan in the language of student cognition’ ensures that the writing of learning objectives are structured as a ‘cognitive act in the context that it will be used’. For example:

L01: Students will evaluate economic ideas.

becomes:

L01: Students will evaluate economic arguments posited in contemporary Australian case studies.

The knowledge domain is factual and conceptual, and the cognitive dimension is to evaluate, but the thinking context is also clearly evident. This is the first stage in reducing overwhelming curricula or ambiguous statements.

In the case of a framework based creative writing unit planned with my colleagues in Year 12 English, we synthesised over 20+ unwieldy knowledge and skills descriptors into eight, each containing a knowledge and cognitive processing dimension, and linked to context.

This immediately provided us clearer line of sight forward. I will use this unit as my key example in the next stage.

Part 2: Identify cognitive inter-relationships and audit for gaps and opportunities

Part two involves identifying the inter-relationships between the cognitive descriptors, which then determines the learning sequence we adopt. This process further permits a common ‘missed step’, of translation, which involve auditing the learning objectives for alignment as well as potential gaps.

The strategy is demonstrated by Dave McAlinden in this explainer video that quite rightly went viral. McAlinden helpfully clarifies how to use Bloom’s Taxonomy to check for alignment and missed cognitive opportunities. This flies in the face of common (misinformed) wisdom about using Bloom’s as a pyramid or checklist, or a template for writing objectives.

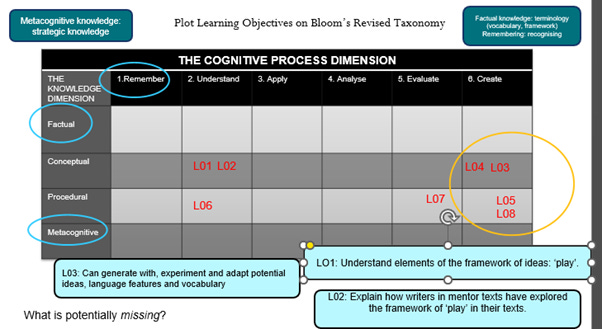

The process involves plotting the learning objectives onto the two dimensional taxonomy table. In the example below, I have placed the eight learning objectives from our English unit.

Plotting things visually allowed us as a team to consider the cognitive attributes of the unit we were planning to teach. Things we noticed from the table included:

Batches of objectives in understanding and creates, focusing mostly on conceptual knowledge (abstract ideas of the framework) and the procedural knowledge of writing.

Gaps in the ‘remember’ cognitive processing dimension, in addition to the ‘factual’ and ‘metacognitive’ knowledge direction.

As stated above, the taxonomy is not a checklist, so there was no obligation to fill all boxes of the taxonomy table. However, the gaps did offer a provocation for an informed discussion amongst our team regarding the role of remembering, factual and metacognitive knowledge in the learning required for our unit. In a subject like English where writing is king, committing facts to memory are easily overlooked, while metacognition is often assumed while teaching procedural knowledge, when it needs to be taught separately. So upon reflection, we constructed additional learning intentions (and resources) focusing on creating knowledge organisers and metacognitive thinking routines for planning and adaptability under time.

We were now in a position to discuss cognitive dependencies and whether the relationship between cognitive skills was bidirectional or unidirectional. For example, is ideas generation dependent on analysis? This of course is not an exact science, and so (like many things in education) we made our ‘best bet’ in sequencing our cognitive skills into a set of developmental levels.

The result of the cognitive audit plus the subsequent planning for alignment with short, medium and long-term assessment and instructional strategies was synthesised into a one-page unit plan, helping us to reign in any curriculum vagueness:

Conclusion

In assisting with the clear delineation of the cognitive domain, the audit enabled us to get closer to ‘elegant simplicity’, which aims to minimise unnecessary curriculum complexity. Furthermore, it gave us anchoring points for focusing our discussion, veering us away from ‘wouldn’t this be fun to do’ in favour of, ‘how can we make things clearer?’ After all, if clarity comes first, there is plenty of time for joyful activities (note the inclusion of ‘I’m just Ken’ in Level 2!)

Having repeated this method recently with a range of colleagues across subjects, including LOTE, PE and Science, I can confirm its utility as a strategy when faced with highly complex tasks. To assist a peer, instructional coaches do not have to be in the same disciplinary field as the teacher. With careful questioning of the one with subjective expertise about the cognitive domain and relationships, a viable sequence of cognitive steps can be extrapolated collaboratively. From that point, the process then relies on a shared language of learning to devise the rest.